“I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.”

I’ve always loved that line from Oliver Cromwell, even if I haven’t always taken its counsel. It’s been lurking in my mental background, though, throughout this essay series. I’ve been banging the drum here in support of some bold claims — capitalism is in crisis, its effectiveness as an engine of social progress is in decline, and a shift toward greater local self-sufficiency is needed to remedy things — that younger me would have strenuously rejected, and that many people today whose opinion I respect do not find persuasive. As I’ve written about previously, anyone who disagrees with me has plenty of evidence to point to. Dynamism may have flagged in recent decades, but a host of exciting new technologies now loom on the horizon. Yes, a new class divide has opened up along educational lines, but it now looks like previous estimates of income inequality were exaggerated, and recently wage growth at the bottom has been outpacing that at the top. And while democratic institutions are under stress here and around the world, they’ve been under worse stress before and they’re still standing.

Of course I have responses to these counterarguments, and overall I find them convincing. But even on those days when I’m feeling shaky and my doubts deepen, there’s one recent global trend that brings me back around to the firm sense that something has indeed gone seriously wrong. And that disturbing trend is the relentless drop in fertility rates around the world below the levels needed to sustain the existing population. The fertility collapse has already led to shrinking populations in Japan, Italy, and China and contributed (along with emigration) to even more precipitous declines in eastern Europe; within a few decades, it now seems highly likely that the total human population will begin to decline.

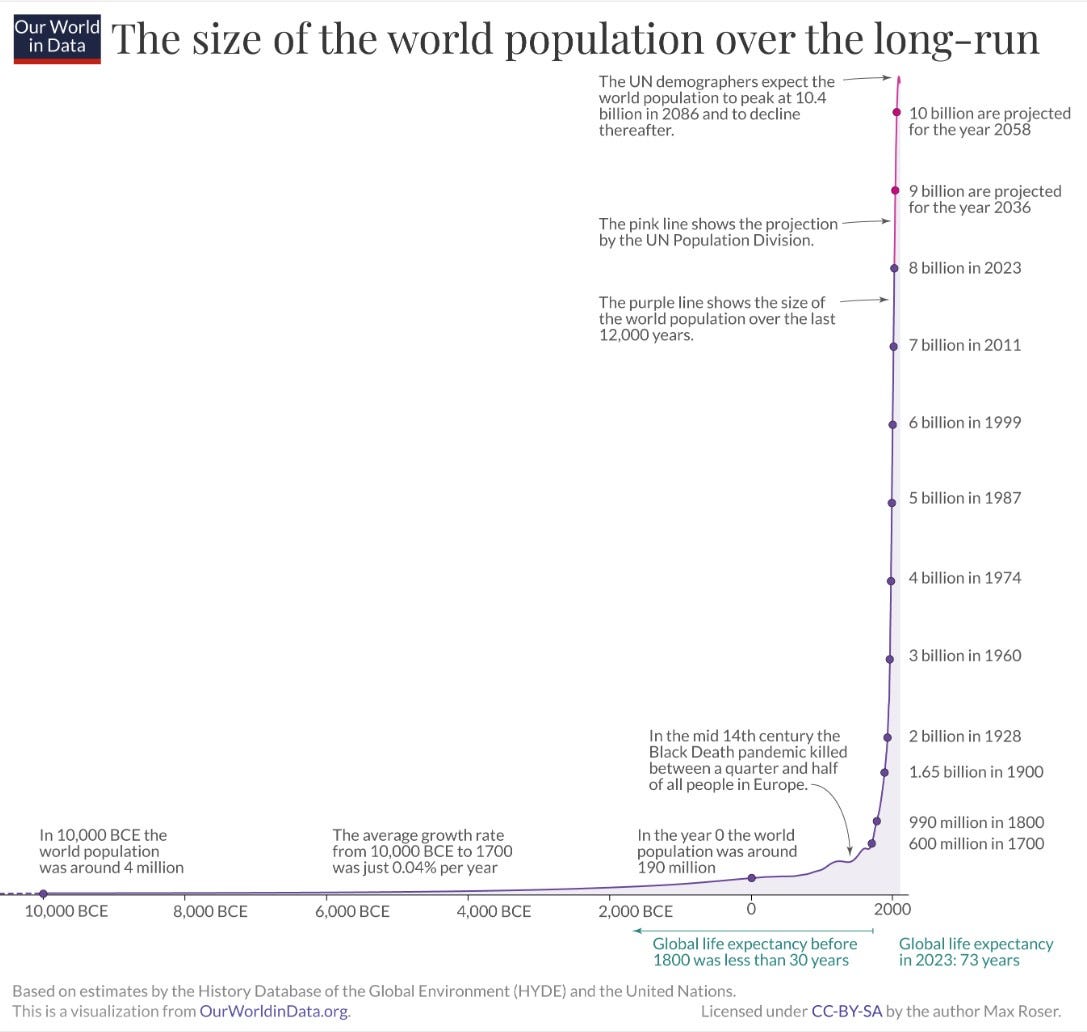

We’ve been slow to grasp the reality of this trend and its profound import — in part because the fall in birth rates was preceded decades earlier by an equally dramatic fall in death rates, made possible by public health measures and modern medicine. The fact that death rates fell first led to a huge runup in global population, from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 8 billion today, prompting widespread fears of overpopulation that gripped the popular imagination during the 1960s and 70s. As such things often play out, the overpopulation panic set in only after the reality on the ground had shifted: the global population growth rate peaked in 1963 and has been falling ever since. When the shift finally started to register (and there are still plenty of people living in the past, haunted by phantom fears of an overcrowded world), it was greeted with widespread relief: the dystopia of a sardine-can planet had been avoided!

The dominant interpretation saw the drop in fertility as an equilibrating response to the earlier fall in mortality. In the past, high birth rates combined with high death rates to keep population stable, inching upwards almost imperceptibly slowly (between the dawn of agriculture in 10,000 B.C. to 1700, the total human population grew by only 0.04 percent a year). High fertility had been necessary to maintain stability, but with a lag families adjusted to the plunge in childhood mortality. In this comforting account, we were in the midst of a “demographic transition” from one equilibrium (high birth rates, high death rates) to another (low birth rates, low death rates) with an intervening bulge in the population.

It's a nice story, and a plausible-sounding one — the only problem is that it just isn’t true. The pacesetter in fertility decline was France, where birth rates plunged starting in the mid-18th century, long before any decline in death rates. Meanwhile, if the fertility drop really were about restoring equilibrium, we would expect to see stabilization at or near the replacement rate (2.1 children per female). But beginning with Japan in the 1970s, we have seen fertility in one country after another falling to sub-replacement levels. At this point, over half of humanity lives in countries with sub-replacement fertility.

And we’ve yet to find bottom. In the United States, fertility fell below replacement level in the 1970s, rallied from around 1990 to 2010 but then has fallen off again. China’s fertility rate slipped below sub-replacement in the 1990s, thanks in part to its one-child policy. China formally ended that policy in 2016, but fertility has subsequently nosedived: from 1.8 in 2017 to 1.09 in 2022. Nobody, though, can match South Korea’s disappearing act: its fertility rate fell from 1.1 in 2017 to 0.8 in 2022, and is projected to hit a mere 0.73 this year — at this rate, the next generation will be roughly one-third the size of the current one!

The worldwide total fertility rate, standing at nearly 5.0 in 1968 when Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb was published, has fallen to 2.3 as of 2021. There is no reason to doubt that the decline will continue past the 2.1 threshold, and that sometime thereafter the total population will begin to decline. Projections from the United Nations continue to portray a relatively rosy scenario, with world population peaking in the mid-2080s at 10.4 billion and remaining basically unchanged by 2100. A 2020 study in The Lancet, by contrast, projects that population will peak in the mid-2060s at 9.7 billion and then drop to 8.8 billion by the dawn of the 22nd century. Given the way the rate of fertility decline has continued to outpace expectations in recent years, my own hunch is that the numbers from The Lancet will end up closer to the mark.

It's hard to overstate what a profound change this will amount to. Humanity has certainly undergone some nasty regional population shocks in the past: the Black Death killed somewhere between a quarter and a half of Europe in the middle of the 14th century, while roughly 90 percent of the indigenous population of the Americas was wiped out by disease over the course of the 16th century. But as the chart below (which follows the U.N.’s current projections) shows, those catastrophes constitute mere blips in the larger story of humanity’s relentless expansion since the advent of agriculture.

I’ve written about the global fertility collapse previously on this blog, focusing on its impact on technological and economic dynamism. The outlook, I’m afraid, is bleak: a society whose birth rate is falling is a society that’s getting older, and there is considerable evidence that an aging population is less innovative and less productive. Already, we’ve seen just a slowdown in American population and labor force growth exacting a considerable toll: according to a 2016 study (updated in 2022), aging reduced the growth in U.S. GDP per capita by 0.3 percentage points between 1980 and 2010. There’s every reason to expect the situation to worsen when the labor force and overall population actually start to shrink. Because of its attractiveness to immigrants, the United States should be able to continue growing for a long time even with sub-replacement fertility — but during the Trump years, immigration fell off sharply (it has staged a partial post-covid recovery). If immigration should revert to those lower levels (not at all unimaginable in light of current political realities), the Census Bureau’s latest projections show that the U.S. population will peak in the 2040s and decline gently to 319 million (it’s currently 335 million).

However important the economic consequences, examining the fertility collapse solely through this lens misses much of its import. The global cultural shift away from childbearing amounts to more than yet another headwind adding to capitalism’s crisis of dynamism; in addition, it represents a major symptom of capitalism’s crisis of inclusion. For most of us, achieving fulfillment in life depends more than anything else on the quality of our personal relationships, yet the incentives and pressures of contemporary economic life push us in innumerable ways, great and small, to prioritize market work and market consumption over family, friendship, and community. As a result, with comforts and conveniences heaped up around us to allure and distract, we have allowed the vital personal bonds that give our lives structure and purpose and meaning to fray and unravel. And there is no personal connection more vital to human flourishing than procreation and childrearing: some individuals can flourish without having and raising kids, but humanity cannot.

I cannot look at what’s happening and reach any other conclusion than that we are witnessing a massive, fundamental failure of the capitalist system. It must be fundamental because it is happening everywhere: across wildly varying cultures and histories, the progress of capitalist prosperity — bringing with it urbanization and rising education levels and expanding opportunities for women – works ineluctably to turn people away from parenthood. And it is fundamental because it goes to the very heart of things. Quite simply, unless the relentless drop in fertility can be arrested and reversed, there is no future — not for Homo sapiens.

I struggle to find the words to convey the scale of the failure, to express adequately what a dispiriting abdication and surrender this represents. After thousands of generations in which the lot of ordinary people was to eke out existence in the ever-present shadow of privation, hemmed in by the harsh constraints of disease and ignorance, we have finally reached the point where most people have the freedom and resources to shape their lives, at least to some extent, according to their own values and preferences – and now, here, at the cusp of a world unimaginably richer and fairer and more open with possibility than we have ever known, we collectively decide that we do not care enough to make this future come true. We do not care enough, indeed, to make any future come true.

Ross Douthat’s verdict seems inescapable: if this isn’t decadence, what else could possibly qualify? His haunting characterization of what’s going on strikes me as spot on:

The retreat from child rearing is, at some level, a symptom of late-modern exhaustion — a decadence that first arose in the West but now haunts rich societies around the globe. It’s a spirit that privileges the present over the future, chooses stagnation over innovation, prefers what already exists over what might be. It embraces the comforts and pleasures of modernity, while shrugging off the basic sacrifices that built our civilization in the first place.

Environmentalists have long charged that capitalism is ecologically unsustainable: our prosperity comes from plundering irreplaceable natural resources and thus cannot last. I’ve always regarded such talk as a kind of self-refuting prophecy, confident that our technological ingenuity will allow us to keep the party going while at the same time repairing the harms that we’ve inflicted on the natural world. We are now faced, though, with the distinct possibility that capitalism is sociologically unsustainable. Capitalism brings unparalleled riches, but those riches in turn induce cultural changes that apparently undermine our capacity to keep pushing forward. We lose our drive to push outward into the physical world, preferring safetyism and NIMBYism and the precautionary principle and historical preservationism; we even lose our drive to extend ourselves outward to connect to other flesh-and-blood people — and with it, our ability to extend ourselves and our civilization into the future with ongoing new generations.

Of course it’s at least theoretically possible that, starting tomorrow, birth rates around the world will start rebounding. Fertility has edged up the past couple of years in the United States; perhaps it’s the start of a global trend. At present, however, there is absolutely no good reason to believe a turnaround is imminent: global fertility rates are not only declining, but the decline has been accelerating. And so, facing the prospect of a major shock to dynamism occurring as a result of a major shock to capitalism’s ability to foster inclusion; and beyond that, more profoundly, faced with the prospect of a humanity so demotivated in the presence of unprecedented riches and opportunities that it can’t mount the effort to share these blessings with children, I cannot escape the conclusion that the capitalist social system, now globally triumphant, is failing globally as an engine of social progress. We need alternatives to mass dependence on the labor market for organizing productive cooperation; we need alternatives to consumerism’s promise of outsourcing everything. I’m not at all sure about the exact form that greater “economic independence” should take, but I’m convinced that a search for alternative social arrangements is called for — and that the search will take us in the direction of revitalized face-to-face relationships and a greater degree of local self-sufficiency.

I’ll stop here for now to keep this essay from going overlong. But I’ll be back next week with further thoughts as I seek to work through some of the implications and strange possibilities raised by the great demographic reversal. And the more I ponder a future from which people are gradually disappearing, the weirder it gets.

I live in Vietnam and I feel the American-centric view of this post (and Douthat's comments) misdiagnose the issue somewhat.

Douthat talks about "rich countries" but as another comment points out that's not correct. Vietnam has a GDP per capita of $4,000 but a fertility rate of 2.013, under the replacement rate. Being rich apparently has nothing to do with it.

Other arguments about NIMBYism also seem to miss the mark. There is no NIMBYism in Vietnam and the economy is growing at 8% but still the fertility rate shrinks. There is dynamism and hunger here that is lacking in America. But it doesn't translate to wanting children. People are future thinking because the current society is poor and who is going to complacent about that?

Talk of cost of childcare also seems to be wrong. There are many countries with free or heavily subsidised childcare and it seems to make almost no difference.

People talk about the "lack of a village" but I'm not sure that's it, either. Most of my neighbours live in multi-generational households but the 1- or perhaps 2-child family has become dominant.

My next door neighbours are a prime example. The grandparents own the house outright. There's not even property tax in Vietnam yet, so the costs as bare bones. The husband and wife live with them. No housing payments. Ample childcare available. Yet they are a one-and-done family. They are adamant about not having more children.

I don't want to pretend I have the answer. I think it likely that, like all problems in the modern world, it is a complicated multi-factor issue. A death of thousand papercuts kind of thing. Car seat laws, restaurants that primarily have 4-seat tables, the pain of getting hotel accommodations when you've got more than 2 kids, the mere logistics of transporting multiple kids to after school stuff in the 99% of cities around the world that aren't a cycling/transit paradise. Even the things I dismissed above are likely contributing factors, even if they aren't smoking guns.

My personal hypothesis is that the problem isn't capitalism per se but consumerism. That human ingenuity has, after several hundred years of exponential innovation, finally created a bevy of choices that surpass what evolution's more plodding pace can provide.

When I travel from Vietnam to America on holiday, the thing that strikes me the most is just how rarely most Americans leave their homes. And who can blame them? Thousand of square feet of perfectly climate controlled privacy, devoid of even the slightest inconvenience. No neighbours who are slightly annoying. No coffee that isn't made exactly how you like it. 500 channels, a dozen game systems, on demand movies from 100 years to choose from.

But it's not just mere consumption. There are 10,000 niche hobbies easily accessible to find what resonates with your soul.

There are so many options to entertain and self-actualise...is it any wonder that our genetic impulse to procreate has been outcompeted?

Raising children is incredibly costly in parental effort, as well as money, and is becoming more so over time. Wishing that people would have more children for the benefit of "the economy" is another version of saying that we would all be richer if people weren't so lazy. Not everyone wants children, and most who do want children are happy with two. The most a pro-natalist policy can and should do is remove some barriers faced by people who want children, but aren't in the kind of stable relationship where this would make sense.

As regards the big picture of humanity, even with an average of one child per woman from now on, the world population would still be in the billions well into next century.