In 1963, the Royal Society in the United Kingdom issued a report complaining about the emigration of British scientists to the United States, lured by higher salaries and better living conditions. The Royal Society referred to this troubling trend as the “brain drain.”

The term has been with us ever since, referring generally to high-skill emigration. In the recent decades of mass immigration to the rich democracies, there has been recurrent concern about the loss of human capital in the poor countries people are leaving. It turns out such concerns are generally overblown: opportunities for high-skill professionals to emigrate to rich countries act as a big stimulus for skill acquisition in poor countries, and most of those people upgrading their skills never leave. That said, the migration of talent can have sometimes big effects: think of the expulsion of the Huguenots from France, or the flight of Jewish scientists from Europe in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

We’re just starting to face up to the fact that the United States, long accused of causing brain drains in other countries, is now experiencing one of its own. Ours is different, though: we’re losing our best and brightest, not to other countries, but to the cemetery.[1] A mounting body of evidence shows that our brain drain is internal: for decades now, Americans have been getting dumber.

I’ve made arguments pointing in this direction in a number of previous essays. I’ve decried the decline in the study of history, lamented our growing addiction to screens, and argued that a media temperance movement is needed to combat screen addiction’s deleterious effects.

Up to now, though, I believe I’ve undersold the problem. I knew that capitalist modernity dramatically increased the demand for brainpower and thereby catalyzed a transformational increase in supply: first through the spread of mass literacy, then through the high school movement and the advent of universal secondary education, and finally through the rise of research universities and the spread of mass tertiary education. (In fact, I wrote a book on the topic .) So while I’ve fretted on these pages that this progress has stalled and may be unwinding, my sense of alarm has been muted by my appreciation of how far we’ve already come. With the level of college completion at an all-time high, standardized math scores for younger students up slightly over the past half-century, and reading scores basically flat, my overall sense has been that recent decades have been a mixed bag of small gains and small reverses. I’ve been thinking stagnation, not decline.

Qualitative and quantitative indicators of decline

What has shaken me out of my relative complacency? Kicking things off was the spate of recent reports about the poor reading abilities of today’s college students and their rapid mass resort to AI for cheating: “The average college student today” and “Everyone is cheating their way through college” are two of the more widely circulating representatives of the genre. If you haven’t read them yet, you should — but here’s an excerpt from the first one:

Most of our students are functionally illiterate. This is not a joke. By “functionally illiterate” I mean “unable to read and comprehend adult novels by people like Barbara Kingsolver, Colson Whitehead, and Richard Powers.” I picked those three authors because they are all recent Pulitzer Prize winners, an objective standard of “serious adult novel.” Furthermore, I’ve read them all and can testify that they are brilliant, captivating writers; we’re not talking about Finnegans Wake here….

I’m not saying our students just prefer genre books or graphic novels or whatever. No, our average graduate literally could not read a serious adult novel cover-to-cover and understand what they read. They just couldn’t do it. They don’t have the desire to try, the vocabulary to grasp what they read, and most certainly not the attention span to finish….

Students are not absolutely illiterate in the sense of being unable to sound out any words whatsoever. Reading bores them, though. They are impatient to get through whatever burden of reading they have to, and move their eyes over the words just to get it done…. Reading anything more than a menu is a chore and to be avoided….

Their writing skills are at the 8th-grade level. Spelling is atrocious, grammar is random, and the correct use of apostrophes is cause for celebration. Worse is the resistance to original thought. What I mean is the reflexive submission of the cheapest cliché as novel insight.

You can find plenty of depressing corroboration of this grim assessment if you have the stomach for it. Like this. Or this. Or this. Or this.

Once you grasp the limited abilities and feeble motivation of today’s students, the arrival of AI looks like the proverbial lightning strike: what was apparently a mighty oak tree is now exposed as nothing more than a rotten shell. It seems that undergraduate education increasingly resembles that old saw about the Soviet Union: the students pretend to learn and the professors pretend to grade them.

The declining ability of undergraduate students is in significant part due to the rising share of people who go to college: now more than 60 percent of high school graduates go on to attend at least some college. But here’s the thing: this greatly exceeds the percentage of people capable of reading serious literature and writing research papers – in other words, capable of doing what used to be thought of as college-level work. The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) measures levels of adult literacy in the U.S. and other countries on a scale of 1 to 5. According to the most recent assessment in 2023, 56 percent of Americans fall into level 2 or lower: in other words, a majority of Americans read at or below the level expected for 6th grade students. And what percent of Americans read at levels 4 or 5 — i.e., able to comprehend serious literature and other difficult texts? About 12 percent. Of course college standards have slipped: the number of people attending college outnumbers the number capable of doing college-level work by several times over!

OK, so maybe we’re not getting dumber at the top; maybe it’s just that we’re diluting the top ranks. Alas, no such luck: dilution is a big part of the story, but not the whole story. The author of this piece in The Atlantic surveyed 33 professors from elite universities and found that the majority have seen a big slide over the years in what their students are capable of:

Anthony Grafton, a Princeton historian, said his students arrive on campus with a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language than they used to have. There are always students who “read insightfully and easily and write beautifully,” he said, “but they are now more exceptions.” Jack Chen, a Chinese-literature professor at the University of Virginia, finds his students “shutting down” when confronted with ideas they don’t understand; they’re less able to persist through a challenging text than they used to be. Daniel Shore, the chair of Georgetown’s English department, told me that his students have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet.

To see this trend, we have to rely on these kinds of qualitative assessments: our main quantitative measures of reading proficiency aren’t picking up declines among top students. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often referred to as “the nation’s report card,” has been assessing American 4th and 8th graders since 1969. Scores for strong readers, those at the 90th percentile, have been basically flat over the lifetime of the test.

I’m convinced that the professors’ qualitative assessments are picking up something real – something that the standardized tests don’t actually measure. Those tests assess comprehension of brief passages, not more than a few paragraphs long. Accordingly, they are incapable of evaluating students’ capacity for “deep literacy” — their ability to immerse themselves in a text and place themselves in ongoing silent dialogue with the author — upon which higher-level intellectual achievement depends.

And it’s not just that standardized tests are missing this intellectual decline — they also seem to be a significant cause of it. Educational “reforms” under the No Child Left Behind Act and the Common Core initiative put overwhelming stress on standardized tests as measures of school performance — and in a classic case of Goodhart’s Law, schools started teaching to the test, progressively reducing and eliminating everything from the school day that didn’t show up in test results. Fatefully, long reading assignments have been a significant casualty. See this snippet from that Atlantic article on functional illiteracy at elite colleges:

But middle- and high-school kids appear to be encountering fewer and fewer books in the classroom as well. For more than two decades, new educational initiatives such as No Child Left Behind and Common Core emphasized informational texts and standardized tests. Teachers at many schools shifted from books to short informational passages, followed by questions about the author’s main idea — mimicking the format of standardized reading-comprehension tests. Antero Garcia, a Stanford education professor, is completing his term as vice president of the National Council of Teachers of English and previously taught at a public school in Los Angeles. He told me that the new guidelines were intended to help students make clear arguments and synthesize texts. But “in doing so, we’ve sacrificed young people’s ability to grapple with long-form texts in general.”

Between these curricular changes inside the classroom and the rise of ubiquitous online distraction, kids are reading a lot less these days. Roughly 40 percent of high school seniors in 1976 reported reading at least six books on their own over the past year, while 11.5 percent said they had read none. These days, it’s the other way around. Here, they’re following in the footsteps of their parents: adult pleasure reading is down significantly as well. According to a 2022 survey by the National Endowment for the Arts, less than half of American adults report reading a single book over the past year.

Standardized tests may be missing the decline in reading ability among top students, but they’re picking it up elsewhere. Average reading scores have held reasonably steady over the decades, but that is masking some recent deterioration at the bottom of the scale. Since 2012, scores at the 10th percentile have dropped by 9 percent for 9 year-olds and 5 percent for 13 year-olds. It appears that the extended school shutdowns during the covid-19 pandemic were especially damaging for kids with less academic ability, probably because being homebound meant a greater drop-off in instruction quality and intellectual stimulation generally. But even if the pandemic experience bears some of the blame here, we also see a similar trend in the PIAAC tests for adults. The percentage of adults stuck at reading level 2 or lower— that is, below the expected reading level for 6th graders — rose from 50 percent to 56 percent between the 2012/14 testing cycle and 2023.

Broader measures of cognitive ability are also flashing warning signs. The PIAAC also measures adult numeracy, and here again there has been a sharp recent decline at the bottom of the scale: between 2017 and 2023, the percentage of American adults in levels 3-5 slipped by only a single point, but the people below level 1 — in other words, people lacking the ability to count, do simple arithmetic, and calculate basic percentages — rose by a shocking 6 percentage points, from 9 percent to 15 percent. According to an ongoing study by Monitoring the Future, the share of American 18 year-olds reporting recent difficulty thinking or concentrating held steady during the 1990s and 2000s before rising sharply in the 2010s. Meanwhile, raw IQ scores, which rose steadily over the course of the 20th century in a phenomenon known as the “Flynn effect,” now are dropping. A recent study by researchers at Northwestern and the University of Oregon examined U.S. test results between 2006 and 2018 and found declining scores in three out of four domains: performance in logic and vocabulary, visual problem solving and analogies, and computation and mathematics all deteriorated, while scores for 3D spatial reasoning continued to show improvement.

A recent article in the Financial Times summarized much of the data reviewed here under the headline: “Have humans passed peak brain power?” As the old Magic 8 Ball used to tell us, signs point to yes.

The literacy continuum

In particular, and most fundamentally, we are in the midst of unmistakable deterioration in the quality of literacy throughout the ranks of society. We tend to think of literacy as a binary — you either have it or you don’t — but that conception sets a low bar: being able to read and write simple sentences, or simply write your name, will suffice. It’s this conception that allows us to talk about the achievement of “universal literacy” in more advanced countries.

But the fuller understanding of literacy — the one used by the PIAAC as it defines various reading levels — sees it as a continuum, with the basic ability to decode letters into sounds and words the mere starting point. From there a reader gradually builds vocabulary, familiarity with increasingly complex syntax, and general background knowledge: as decoding and word comprehension become automatic and no longer require conscious effort, effort can be devoted instead to following a twisting, turning narrative with a growing cast of characters or a long, involved chain of reasoning. The reader enters into a silent dialogue with the author — in fiction, suspending disbelief, identifying with the characters, and seeing the action play out in one’s own visual imagination; in nonfiction, teasing out implications, comparing and connecting what is read to one’s background knowledge, questioning one and then the other when the two don’t align, and ultimately deciding what to reject and what to integrate into one’s ever-developing knowledge base. This is what literacy researcher Maryanne Wolf calls “deep reading”: “that ‘fertile miracle of communication’ that happens when readers use all their cognitive and linguistic capacities to ‘go beyond the wisdom of the author’ to generate their own best thoughts — for themselves and sometimes for us all.”

As Wolf explains, deep reading creates a new platform for thought inside the brain — one capable of dramatically more complex thinking than can be achieved through solely oral communication. The possibilities for analytical sophistication and logical rigor are revolutionized by having a permanent written record that can be returned to again and again by readers separated in both time and space; the capacity for an entirely new form of literary characterization — creating fully realized imaginary individuals whom you often feel you know better than many actual people in your life, and who can stay with you as ongoing inspirations or object lessons — is likewise achieved.

Written language, in other words, enables levels of cognitive complexity that are simply unattainable in oral communication. It is, quite simply, the cognitive foundation on which all the achievements of civilization ultimately rest. Law and bureaucratic organization, contracts and other commercial arrangements, science and engineering, even the spread of ethical, “Axial Age” religions — all were made possible by literacy’s platform for a large-scale, long-term division of intellectual labor.

We know no other world than the one that literacy built, and so we take it for granted and assume it is our birthright. But it most assuredly is not. Humans are hard-wired for oral language: young brains are built to soak it up, and even people with mental disabilities learn to speak and understand. But literacy is something else entirely. Literacy is a cultural achievement, and a profoundly unnatural one at that. Homo sapiens first emerged some 300,000 years ago, and began to exhibit what we call “behavioral modernity” (complex tools and symbolic communication) around 70,000 years ago — but the first writing did not develop until a little over 5,000 years ago. And until very recently, reading and writing were the preserve of just a tiny minority: only in the past half-century or so, a relative eyeblink in the history of our species, has the rate of basic literacy for humanity as a whole moved past 50 percent.

Literacy, then, is a skill that must be learned, developed, and maintained. And there’s only one way to do that: sustained, effortful practice. There’s been plenty of quibbling about the “10,000 hours rule” popularized by Malcolm Gladwell, but the basic intuition is inarguable. How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.

And here we come to the fundamental cause of America’s internal brain drain: the practice of reading in this country has been in long-term decline for over a half-century now, ever since the rise of television. The whole nature of our communicative culture has changed: the agentic, immersive print culture of long-form text has been displaced and marginalized, first by the passive TV culture of absorbing video images, and now by the hyper-distracting online culture of memes, short videos, and snippets of text. Adult literacy has atrophied accordingly, and now we’ve turned away from inculcating deep reading in schools. The advent of AI, at least based on how it’s being used so far, looks poised to deal another heavy blow to the culture of literacy.

Here's how Adam Garfinkle summarized the situation in his superb 2020 essay “The Erosion of Deep Literacy”: ”A greater percentage of Americans may be deep literate in 2019 than in 1819 or 1919, but probably not than in 1949, before television, the internet, and the iPhone.”

I read this article when it came out, and I nodded along in agreement at the time — but it’s only recently that I really grasped the implications of that stark conclusion. I don’t think there’s any way to spin this: the declining quality of literacy, driven by the declining popularity of deep reading, constitutes cognitive regress. It required spectacular genius to devise and develop the new technologies of post-literate distraction, but their effect on the rest of us has been to make us dumber.

Here’s the basic equation: the quality of our thoughts is a function of the quantity of demanding reading we undertake. The reason is that written language enables levels of cognitive complexity that are simply unattainable in oral communication. Look at the chart below from the fascinating article “What Reading Does for the Mind” by Anne Cunningham and Keith Stanovich. To compare the complexity of written versus spoken language, words were ranked according to the frequency of their appearance in a large selection of texts: it was then possible to look at the median frequency of words used, and the appearance of rare words per 1,000 words encountered, in various different forms of oral and written communication — in particular, printed texts, television programs, and adult speech.

I don’t think most people have any idea of the dramatic disparity between written and oral language. Normal speech between college-educated adults and prime-time adult TV shows feature similar levels of vocabulary — and it’s below the level of preschool books! Newspapers (remember them?) include rare words at roughly three times the frequency. Rarity here has been defined as words outside the mostly commonly used 10,000 — roughly the vocabulary level of 4th to 6th graders. If you’re going to build your vocabulary beyond that level — that is, if you’re going to acquire the building blocks for more nuanced, sophisticated, and complex thought — you’re going to need to read regularly.

Cunningham and Stanovich refer to studies that estimate the cumulative number of words that kids read per year at various percentiles of daily reading time. Kids at the 90th percentile read 1.8 million words a year on their own, compared to only 8,000 words a year for kids at the 10th percentile. “To put it another way, the entire year’s out-of-school reading for the child at the 10th percentile amounts to just two days reading for the child at the 90th percentile!” Cunningham and Stanovich conclude. “These dramatic differences, combined with the lexical richness of print, act to create large vocabulary differences among children.”

Reading challenging texts creates opportunities for learning that cannot be replicated anywhere else. Reading a lot isn’t just something smart people like to do; a big reason they’re smart is that they read more than other people. In their survey article, Cunningham and Stanovich review the evidence that reading volume is itself a cause of improved cognitive performance. In their own research, they have found that, even after controlling for general intelligence and verbal ability (ability to decode letters into words), more reading led to bigger vocabularies for elementary school students. Looking at college students, they found that reading volume contributed significantly to improved vocabulary, general knowledge, spelling, and verbal fluency — even after controlling for general intelligence and reading comprehension levels. In another study of college students, they bent over backwards to isolate the effects of the quantity of reading from readers’ overall abilities — controlling for high school grade-point average as well as scores on an intelligence test, a math test, and a test of reading comprehension. After testing these college students on various domains of general knowledge, they concluded that reading volume accounted for 37 percent of the variance in scores.

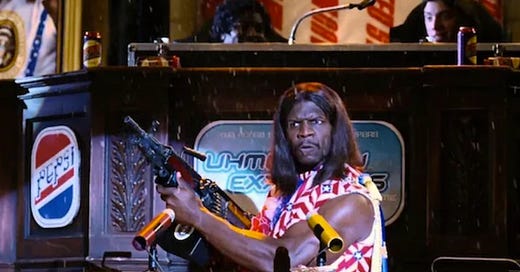

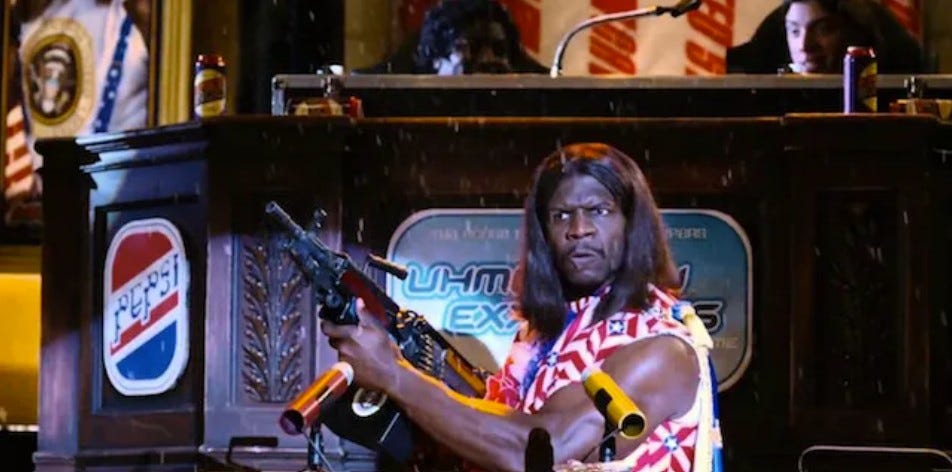

If you want a good analogy to what we’ve doing to our brains by substituting TV and online distraction for books, magazines, and newspapers, look at what we’ve done to our bodies over the same time period. Despite having better access to healthy and nutritious food at affordable prices than at any point in history, we have chosen instead to stuff our faces with addictive junk food — and as a result, over 40 percent of us are now obese, nearly 10 percent of us morbidly so (compared to 13 percent and 1 percent, respectively, in the early 1960s). Likewise, despite spending more time than ever in school and having unparalleled access to all the world’s knowledge at one’s fingertips, we have instead chosen to spend ever-more hours in the day consuming addictive junk food for the brain. You can call the larger process — the misuse of affluence to degrade body and mind instead of uplift them – WALL-E-fication.

Too dumb for democracy?

Once you face up to the fact that American society has actually been getting dumber, you can’t help but connect the dots and see the effects in today’s dysfunctional politics. What’s so striking about the second Trump administration isn’t just the extravagant corruption, mendacity, and cruelty — it’s the over-the-top stupidity on parade every day, spreading a thick layer of insult on top of all the injury. The first administration was bad enough — think injecting disinfectant to treat covid — but this time around almost all the conventional GOP types from last time have been replaced by true believers and cynics on the make. And so we have the rank economic illiteracy of the “Liberation Day” tariffs and the absurd TACO two-step that has followed. A director of national intelligence suggesting the need for briefing videos for a president who refuses to read. A secretary of homeland security who doesn’t know what habeas corpus means. A FEMA director who had never heard of hurricane season. A secretary of health and human services who opposes vaccines and takes his family swimming in a fecally contaminated creek. And as for the mentality that sees all this and cheers, it’s also brought us QAnon, hundreds of thousands of preventable covid deaths, and now measles outbreaks. The makers of Idiocracy got the timeline all wrong, and they imagined the cause as dysgenics rather than mass distraction — but what they offered up as broad satire less than two decades ago now seems uncomfortably on the nose.

I have described the current state of affairs as a legitimacy crisis for liberal democracy — one that is now confronting countries around the world. Quite simply, a critical mass of the electorate has lost faith in governing elites and established institutions and is in the mood to burn it all down. I’ve identified three possible contributing factors, all of which I believe are in play: first, elite failures that reduce their trustworthiness; next, a media environment that magnifies elite shortcomings as never before; and finally, a reduced capacity for trust on the part of the public.

On that last point, I have focused on the affluence-induced cultural shift toward self-expression values and their tendency toward a corrosive skepticism of any kind of authority. I still think that’s an important part of the story, but I would now add an important additional factor: our collective cognitive regress means that more and more people are either unable or unwilling to maintain those abstract convictions and loyalties that make for good democratic citizenship. The separation of powers, the rule of law, due process, civic equality, democratic forbearance — for an increasingly large section of the electorate, this is all just incomprehensible gobbledygook that goes right over their heads.

Consider Jonathan Rauch’s brilliant article in The Atlantic that characterizes Trumpism as the return of “patrimonialism.” What we’re seeing isn’t classic authoritarianism, which is typically heavily bureaucratized and intent on building and maintaining institutions. Authoritarianism and democracy represent alternative forms of modern government rooted in what Max Weber called rational legal authority, in which legitimacy is vested in impersonal institutions and rules. Trump, following the example of Vladimir Putin, is resurrecting an older, premodern style of governance:

Patrimonialism is less a form of government than a style of governing. It is not defined by institutions or rules; rather, it can infect all forms of government by replacing impersonal, formal lines of authority with personalized, informal ones. Based on individual loyalty and connections, and on rewarding friends and punishing enemies (real or perceived), it can be found not just in states but also among tribes, street gangs, and criminal organizations.

In its governmental guise, patrimonialism is distinguished by running the state as if it were the leader’s personal property or family business.

Rauch doesn’t really offer an explanation for why this this retreat to earlier forms of political authority is happening, but I now believe that at least part of the answer lies in America’s internal brain drain. Modern sources of authority are simply too abstract for many of our citizens to grasp and uphold. Neil Postman called it over four decades ago, before the internet and social media made their own perverse contributions: “Under the governance of the printing press, discourse in America was different from what it is now — generally coherent, serious and rational; … under the governance of television, it has become shriveled and absurd.”

Updating and expanding Postman’s analysis, Adam Garfinkle has recently rolled out a book-length manuscript on his Substack that offers an in-depth investigation into what he calls today’s “Age of Spectacle.” The cognitive changes wrought by the modern media environment are central to the story he tells. Adam, who I’m happy to report is now a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center, is presently attempting to wrestle this rather sprawling manuscript into something more compact. In the meantime, if this essay of mine resonates with you, I heartily encourage you to visit his Substack for much more on these subjects.

The cognitive regress I’ve described here has been occurring slowly and subtly over the course of decades — but now comes the advent of AI, which, in its present incarnations at least, looks poised to accelerate our national brain drain by helping to ensure that young people’s cognitive potential never gets realized. Students in high schools and colleges across the country are now relying more and more on ChatGPT and other large language models to “automate” the learning process (i.e., read books and write papers about them), but the joke’s on them. Learning cannot be automated; it comes only to those who are willing to do the necessary work. And consequently, we risk raising even our best and brightest to be post-literate.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m about as far from a Luddite as you can get. The current AI models are breathtaking marvels whose capabilities at present — and no one thinks this is the end of the road — open up dazzling possibilities for genuine and transformative progress. I’m using AI more and more — not to write or edit (Substack’s main attraction is the ability to offer your own, unedited thoughts to the world!), but as a research tool and, with increasing frequency, as a drop-dead-brilliant virtual colleague whom I can bounce ideas off of and argue back and forth with.

For people like me — people who have already done the work of converting their innate “plastic” intelligence into a considerable body of hard-won “crystallized” intelligence — today’s LLMs and their successors offer an amazing amplification of our cognitive powers. For us, they can act as a kind of Iron Man suit for the mind. But for developing minds that haven’t yet put in the work, AI use along current lines subverts the realization of cognitive potential. Instead of slipping on Iron Man suits, they get locked into the hoverchairs from WALL-E. The historian Timothy Burke explains:

[T]he most useful deployment of current and near-future generative AI in research and expression absolutely requires that you already know a great deal. This is not a new problem in research or in creativity. You couldn’t use a card catalog without knowing what you were looking for as well as knowing what a card catalog is. You couldn’t use Google search back at its height of effectiveness without already knowing enough to iterate your keywords, refocus your searches, or mine out the materials you consulted from one search to refine the next.

The problem with the hype about generative AI, and its headlong insertion into many tools and platforms, is that it is brutally short-circuiting the processes by which people gain enough knowledge and expressive proficiency to be able to use the potential of generative AI correctly.

I continue to hold out hope that the best solution to the bad effects of AI will be better AI. There is immense potential, I believe, in AI tutors that offer individualized, always available, and infinitely patient instruction. Such tutors would be designed to guide young people — and adult learners as well — through the effortful process of gaining knowledge and developing skills. We know that one-on-one tutoring is dramatically more effective than classroom instruction — the problem has always been that it’s impossible to scale. With AI tutors, that constraint disappears.

That’s not the AI we have now. But if we are going to arrest and reverse our cognitive decline rather than speed it up, that’s the AI we need. Meanwhile, we’ve started to get phones out of the K-12 classroom; that’s good, but now we need to start getting books back in them. And all of us need to recognize that regular exercise is just as necessary for the mind as it is for the body — and adjust what we devote our attention to accordingly.

[1] The madness of Trump’s second term may be triggering a traditional, emigration-based brain drain as well.

I share your concerns about the "dumbing down" of the population. With regard to primary and secondary education, I think it's worse than you present. In Connecticut, for example, the state and its school districts have an explicit policy of requiring no mastery of any subject for grade advancement. There was a small sensation a few months ago when a recent honors graduate of Hartford Public High School, now attending the flagship University of Connecticut, testified that she can not read at all. The state and city have promised an investigation, but have shared no results. This was not an oversight; neither Hartford nor any other school district I know of requires students to master material in order to advance to the next grade.

I'm not sure, though, that the dumbing down is contributing to the anti-elitism of today's Trumpian politics. You say that it's a worldwide phenomenon, and there are certainly similarities between the US and Europe, but I'm not aware of similar trends in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, or Latin America. I think the elites have earned the distrust of the voters, due to clear (but different) causes in the US and Europe.

In the US, I think the elites have discredited themselves in several ways. They wrecked the financial system by allowing overly risky arrangements with incomprehensible instruments; the motivations were obsessive fixation on expanding homeownership (from politicians), mixed with greed and the opportunity to gamble with other people's money (for the financiers and traders). The result was a public fiasco, massive spending required to bail out the institutions, and an obvious perplexity on the part of government officials, unable to explain the causes of the collapses or future actions that could prevent a repeat. When covid started, the experts changed their recommended actions without explanation, supported economic shutdowns with dubious value, allowed exemptions from preventive measures for social justice protests, and shut down and ostracized experts who disagreed with any of the recommendations or questioned the claim that the origin of the virus was zoonotic. Now it appears that the dissenters were more right than the certified experts; right or wrong, though, their claims deserved serious treatment rather than suppression. Along the way, the elites decided that boys should be admitted to girls' sports leagues and locker rooms if they wanted, that the only way to treat people fairly is by permanent racial quotas, that open borders is a moral imperative, that radical restructuring of the economy to eliminate fossil fuels is an urgent necessity, and that certified truth-tellers were obligated to purge "misinformation and disinformation" from public fora. They implemented this agenda with no democratic mandate, often in violation of the law, and often while lying about their means and objectives. These elites have utterly discredited themselves, and will need a long time to regain public respect, once they decide to try.

In Europe, the foundational problem was a commitment to "ever closer union," which they interpreted to give more and more authority to EU-level bodies with no democratic legitimacy or accountability. When they attempted to codify this approach with the Constitution for Europe, the Constitution was rejected in several member countries, including France, generally seen as the most pro-EU country in the union. There was similar recklessness with the financial system, but in order to paper over insolvent governments more than to subsidize homeowners. Covid was somewhat less contentious than in the US, but there was generally little acknowledgement of the limitations of the expert's knowledge or the uncertainty that should have been attached to their recommendations. They pursued a similar open-borders agenda, again without democratic legitimacy, and lied to cover up shocking crimes committed by some of the immigrants. In the UK, they had similar racial issues to the US, again without public support. They were more enthusiastic for the trans ideology than their US counterparts, again without democratic legitimacy or public support. Most EU countries have been much more enthusiastic about the Green agenda, spending enormous amounts of money and resulting in higher energy prices with minimal or no effects on carbon emissions. European elites also have discredited themselves, and will need a long time to regain public respect.

I'm not defending screens and AI, which may be accelerating the dumbing down of the population. But our political problems will remain even if the dumbing down reverses next week.

Sorry, bro. This piece was like soooo long and theres like no vdo to watch. Just cant be bothered, ya know?