Can faith be restored in a disillusioned world? Traditional modes of engaging the sacred have lost their hold on people’s loyalties, and our current hyper-individualized improvisations are not equal to the task. The soul sickness of despair has taken hold and is spreading, gnawing away at all the vital connections that make life worth living.

As to whether traditional forms of religion can be revived, or new forms established, that are capable of rebinding what has fallen apart, neither I nor anyone can say. Religious awakenings and great cultural movements cannot be scripted or legislated; they await some spark of inspiration whose specific nature can never be predicted in advance.

But I believe there are things we could do to make the intellectual ground more receptive to such a spark. If we change the way we think, we may find that we have awakened our capacity to believe.

As I argued in my last essay, American society is suffering from a contagion of despair — feelings of alienation and homelessness, of being an unwelcome stranger in one’s own land. This sense of estrangement began on the left, with the emergence of a mass “adversary culture” in the 60s, but more recently it has jumped the ideological divide and infected the right as well.

I believe that this alienation is based on deep-seated intellectual confusion, rooted in the manifestly incorrect idea that people are naturally pure and good and that all our problems are due to oppressive hierarchies and unjust authority. This is what I call the romantic heresy; it is the acid bath in which all our most precious attachments, to each other and to the sacred, are presently dissolving. If we can pull this untenable assumption out into the open, interrogate it and expose its errors, and then reexamine our place in society in a new light, perhaps we can reason ourselves back toward faith.

This introspection and reappraisal need to begin in the progressive quarters of American society. It’s true that, at present, problems on the right are more urgent: despair on the right is burning with a nihilistic fury that threatens to wreck our constitutional order. In the short term, then, we have to resist this fury, outvote it, and outlast it. But over the longer term, our hopes for genuine renewal — political, spiritual, civilizational renewal — depend on the leading elements of society, those who wield the lion’s share of cultural and economic power and who are the primary initiators of change and development. The right’s role is essentially reactive: it can react constructively to critique and moderate the proposals of the left, or it can strike out blindly and throw sand in the gears. But it is the destiny of the left to take the initiative and set a new course. If our society is to recover the internal confidence that makes religious and civilizational vitality possible, the recovery must begin in those precincts of society where that confidence was initially shaken and lost.

I want to talk here about restoring civic faith — faith in our modern way of life, faith in our country — but I think it’s best to start by explaining what I mean by faith at the religious or existential level. Existential faith is not ultimately a belief, but rather a choice — the elemental choice that expresses an individual’s fundamental relationship with the world around him. It is the choice, in the words of Viktor Frankl, to say “yes to life, in spite of everything.” Frankl, a psychiatrist who survived years in Nazi concentration camps, was able to persevere by seeing that meaning in life — reasons to go on living — could be found even under the most appalling circumstances imaginable. According to Frankl, the main sources of meaning in normal life are work (creativity, dedication, usefulness to others) and love (not only in the form of relationships, but also experiences — say, of music or natural beauty). But even when opportunities for work and love have been stripped from you, there is still meaning to be found in suffering — which, sooner or later, everyone will have to endure. “Everything can be taken from man but one thing,” Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning: “the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Ground down by brutal, unremitting pain and hardship, many could find nothing more to expect from life. Frankl, though, said this was the wrong question: “It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.” Even when a person’s life has been reduced to nothing but suffering, “his unique opportunity lies in the way he bears this burden.” Bearing his burden with courage and dignity — with the idea in the back of his mind that his loved ones would be proud of him if they saw how he faced this great trial — was what life was expecting of Viktor Frankl. He said yes, in spite of everything.

Living in the peaceful, prosperous United States, we are worlds removed from the kinds of horrors Frankl was forced to endure. Yet all of us have been touched by tragedy and loss, and some of us have been well and truly bludgeoned by them. By the grace of faith, we make it through these dark times by recalling and giving thanks for all the many blessings we have to be grateful for. We say yes to life, in spite of all its difficulties and disappointments.

With the decline of organized religion, we have been losing access to those traditional communal forms through which this existential faith is shared and expressed. When or whether we will return to shared, communal experiences of the sacred, whether through traditional religious forms or new ones, remains to be seen. We can no more predict the future of religion than we can the future discoveries of science.

But there are other, sublunary forms of faith that do not rely on religious inspiration — namely, faith in our way of life and faith in our country. These do not connect us to the transcendent realm of ultimate questions, but they can bind us to one another, to our past, and to our future. Burke famously called society “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Faith in this context consists of acknowledging that partnership and one’s own membership in it. It means saying yes, in spite of everything.

Our contemporary way of life, pioneered by the United States but now global in extent, is the way of progress. For progressives to uproot the error that has led them and all of us astray, they need to be worthy of their name: progressives need to rediscover faith in progress.

A widespread naïve faith in progress arose in the North Atlantic world during the 19th century, only to be shattered in the 20th by the bloodletting and destruction of two world wars and the ensuing threat of nuclear annihilation. But this was a shallow faith, maintained in happy, ignorant denial of progress’s two-edged sword.

A mature and durable faith in progress does not mean blindness to the dark side of increasing knowledge and power and riches. It does not rest on any facile assumption that everything will work out for the best. The words of Reinhold Niebuhr are worth recalling here: “There is therefore progress in human history; but it is a progress in human potencies, both for good and for evil.” There is no final, perfect equilibrium toward which we are striving; there is no expectation of ultimate victory.

Faith in progress requires only that we recognize the fact of progress as a historical reality, and the potential for further progress as a future possibility. With appreciation of humanity’s past accomplishments come pride and gratitude; with awareness of future possibilities comes the responsibility to be worthy of our good fortune and leave the world at least a little better than we found it.

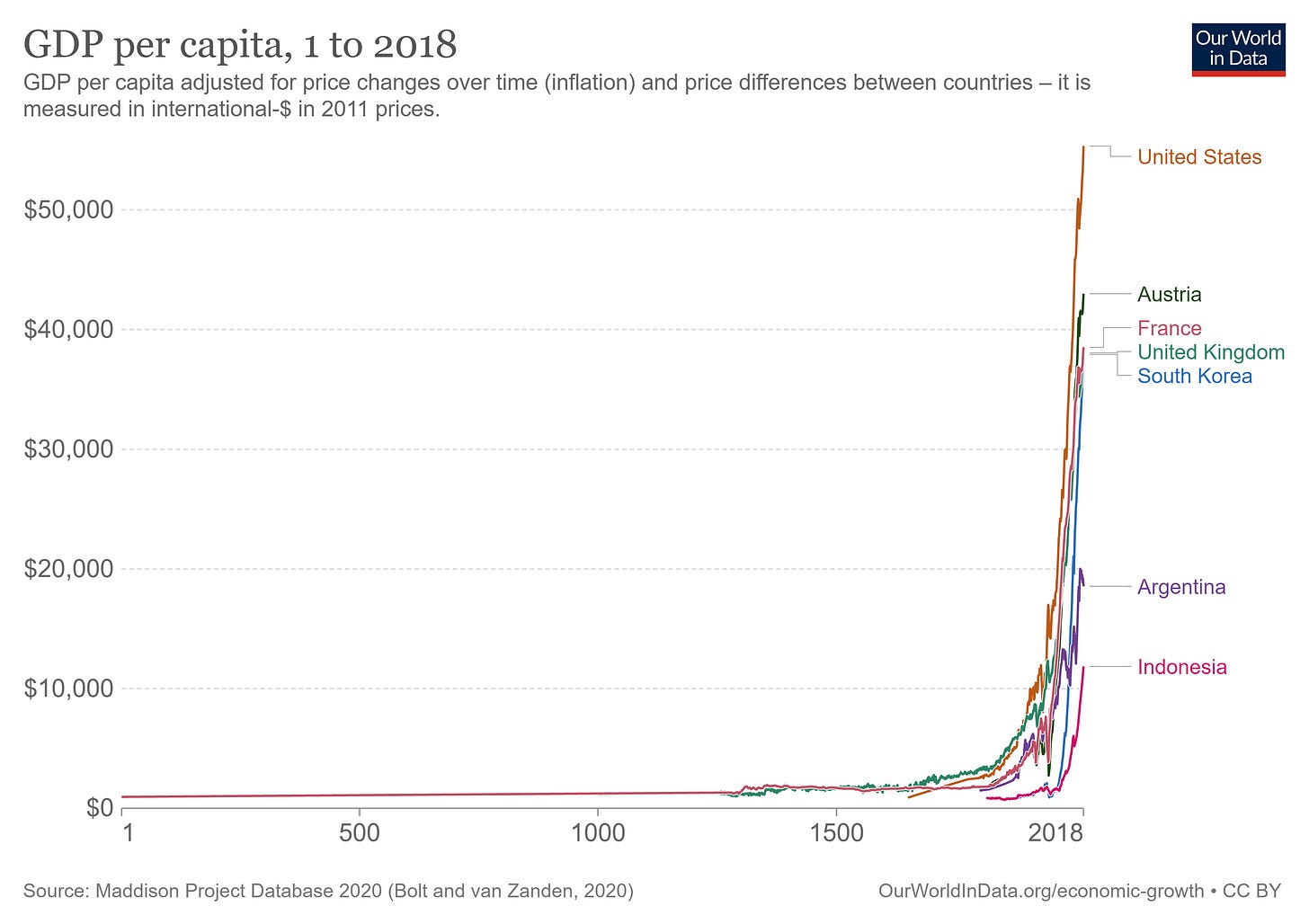

As to the fact of progress, a picture is worth a thousand words:

In lieu of more pictures, or more thousands of words, I’ll simply note that I could have added similar graphs — with lines hugging the x-axis from as far back as it goes until a century or two ago and then zooming nearly straight upward — for population, literacy, and life expectancy. And over the same time period as those near-vertical ascents in material wellbeing, we have also seen the birth and spread of popular self-government under the rule of law, the eradication of chattel slavery, and the emancipation of women.

This is the reality of human progress. The gradual development and realization of human capacities for creativity and connection have been a throughline of the human story since the emergence of our species, but the pace in the modern era is unlike anything ever experienced before. We are in the midst of an astonishing revolution of increasing knowledge and material betterment — the greatest change in human affairs since the dawn of agriculture ten millennia ago. And the revolution, now global in extent, still has no end in sight.

It is an important clue as to the nature of our current problems that the fact of human progress is not widely known or appreciated. Surveys reveal that most people simply have no idea how much better things are now than they were before — and, in particular, about the astonishing recent gains in human welfare outside the North Atlantic region. And this isn’t purely passive ignorance, either. There is considerable resistance to acknowledging improvement in almost any domain — from global poverty to the resource-intensiveness of economic growth to air and water quality to American race relations — for fear that doing so amounts to excuse-making for the status quo.

It is worth dwelling on our state of actively maintained ignorance and what it says about us. In a healthy culture, the revolution of the past couple of centuries would be common knowledge: schoolchildren could be expected to recite rhymes about it, as we once did about when Columbus sailed the ocean blue. The fact that most people are unaware of the real record of human progress means, quite simply, that we are lost. We don’t know where we are in history, the unique position we occupy. We don’t know the special privilege that we enjoy, or the weighty responsibility that we shoulder.

Once we face up to the fact of progress, the perverse falsity of the romantic heresy becomes obvious. The powers and riches that we enjoy and take for granted are the legacy of a massive mobilization of organization, planning, self-discipline, focus, and diligence — the antithesis of romantic antinomianism. And those powers and riches are the very reason that we are able to enjoy the luxury of a romantic streak running through our civilization. The romantic ideal of liberating the individual from oppressive constraints has indeed been progressively realized — but through mass submission to a new set of looser but still-binding constraints. Real progress is an intricately orchestrated symphony, not a cacophony of barbaric yawps.

Resistance to acknowledging our immense progress frequently takes the form of denigrating the significance of past accomplishments because they were the handiwork of flawed people. But such criticism ignores what it actually means to make progress. All progress, all movement toward the higher and lighter, is necessarily a product of something lower and darker — where else could it come from? If we deny the fact of progress because it emerges from a flawed past, then in the same breath we are denying the possibility of future progress because of its roots in a flawed present.

We live inside the flux of history and there is no escape: we can rise higher through history, but we can never stand outside it. So yes, capitalism was mixed up with slavery and colonialism, democracy was mixed up with oppression and aggressive war, the Enlightenment was mixed up with scientific racism, feminism was mixed up with eugenics, environmentalism was mixed up with nativism and fascism — but what of it? In history’s vast tapestry, everything is mixed up with everything else.

In that wonderful meditation on the tragedy of politics, Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, the theme of good and evil’s uncomfortable proximity comes up again and again. Here’s a representative passage:

“Dirt’s a funny thing,” the Boss said. “Come to think of it, there ain’t a thing but dirt on this green God’s globe except what’s under water, and that’s dirt too. It’s dirt makes the grass grow. A diamond ain’t a thing in the world but a piece of dirt that got awful hot. And God-a-Mighty picked up a handful of dirt and blew on it and made you and me and George Washington and mankind blessed in faculty and apprehension. It all depends on what you do with the dirt.”

The corrupt politician Willie Stark is speaking here, rationalizing his own dirty dealings. He is wrong, of course, that the world’s complexity absolves him of responsibility for his many crimes and transgressions. But he is right that there is no escape from the complexity of the world and its legacy to us. As Stark’s former aide and the book’s narrator, Jack Burden, observes in the novel’s concluding line: “We shall go out of the house and go into the convulsion of the world, out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.”

Facing up to the reality of progress carries with it two emotional corollaries. Recognizing the immense amount of progress already achieved, we should feel profound gratitude; recognizing the possibility of further progress in the future, we should feel a deep sense of obligation to help bring it about. If you grasp the deep recesses of the human past, and the relative eyeblink during which modern conditions have obtained, it’s just impossible not to be struck by how absurdly lucky you are that your character’s appointed hour on the stage is now.

Gratitude, in my view of things, is the cardinal virtue: saying yes to life, staying mindful of the blessings it brings, orients us properly in all that we do, encouraging us to reach out and connect to the world and others and to hold ourselves open when they reach out to connect with us. Feelings of gratitude naturally spill over into the desire to pay it forward — in this case, so that your children and grandchildren can experience the same kinds of ongoing improvements that you were lucky enough to enjoy. And if you take the time to figure out how progress actually occurs, you’ll realize that you can’t pay it forward by taking stands and signaling virtue. No, you must participate in, or in some way actively support, real-world efforts to actually get things done. A true ethos of progress steels us to resist the performative temptation.

We commit to trying to improve the world even knowing that progress is always double-edged. There will be unintended consequences: solving one problem will create others, because that’s the way the world works. There is no final destination, no final safe harbor. There is only the choice between growing and dying, and we choose to side with life and its growth.

If progressives can rediscover faith in progress — if they can learn to say yes to progress, in spite of everything — they can recover their faith in their country as well. For what is America, at its best, but the embodiment of the spirit of progress? The United States has been the central proving ground for the two great liberating revolutions of modernity: liberal democracy and industrialized mass production. Leon Trotsky’s verdict was correct when he rendered it over a century ago, and it remains correct today: America is “the furnace where the future is being forged.”

As faith in our new country took shape, it assumed religious trappings with the conception of America as a “covenant nation.” Just as the children of Israel became the chosen people by entering into a special covenant with God, so America has assumed a special role in the world — in Lincoln’s wonderful phrase, “his almost chosen people” — through its commitment, at the moment of its founding, to the high ideals memorialized in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. And as the civil religion tradition unfolded, the Civil War assumed a special significance as the reconsecration of the country’s original covenant and expiation, through fire and blood, for its failures to live up to it.

In his famous essay on the American civil religion, the sociologist Robert Bellah argued that:

The civil religion at its best is a genuine apprehension of universal and transcendent religious reality as seen in or, one could almost say, as revealed through the experience of the American people. Like all religions, it has suffered various deformations and demonic distortions. At its best, it has neither been so general that it has lacked incisive relevance to the American scene nor so particular that it has placed American society above universal human values.

In a foreword written for a subsequent reprint of that essay, Bellah stressed that “I conceive of the central tradition of the American civil religion not as a form of national self-worship but as the subordination of the nation to ethical principles that transcend it in terms of which it should be judged.”

In his recent book American Covenant, Philip Gorski, also a sociologist and Bellah’s former student, upholds the “prophetic republicanism” of American civil religion as the basis for reclaiming the country’s “vital center” in this time of toxic polarization. Gorski follows Bellah in sharply distinguishing between the civil religion tradition and that of religious nationalism. “At its core, religious nationalism is just national self-worship,” Gorski writes. “It is political idolatry dressed up as religious orthodoxy. Any sincere believer should reject it, remembering that the line between good and evil does not run between people or nations; it runs through them.”

Since the 60s, faith in American civil religion has been wrecked on the shoals of disillusionment. As I wrote in my last essay, the critical spirit of the mass adversary culture was able to break through the complacency of “national self-worship” and bring into much wider awareness the darkest and most tragic elements of the American past. Among progressives, this revisionist understanding of our history has led to an ebbing — and sometimes, an outright renunciation — of patriotism, in the latter case dismissing it as nothing more than another species of bigotry.

The progressive retreat from faith in America is far from universal: Barack Obama is the most prominent recent representative of the patriotic counter-current. But it is widespread enough to exert a strong and disfiguring influence on the nation’s center-left, and thereby on the country’s whole political trajectory. And it is rooted in deep-seated intellectual and spiritual confusion.

To lose faith in one’s country because there are crimes in its past and even its greatest leaders have been flawed is to demonstrate a total lack of familiarity with the Biblical sources of American civil religion. The Old Testament, the story of God’s chosen people and the model for America’s self-understanding as a covenant or creedal nation, is brimming with stories of great crimes and moral failures. The heroes in the Bible are typically presented as singularly unpromising before God selects them as instruments of his will, and often as not continue to sin greatly even afterward. The children of Israel are the chosen people not because they are any less fallen than any other people on Earth; they are chosen by virtue of the bargain they have struck with God, the sacred commitment they have made and to which they return again and again even as they repeatedly fall short.

Faith in American civil religion calls us, not to ignore the sins of the past, but to see ourselves as special, as an “almost chosen people,” because of our founding ideals, and because of our ongoing, imperfect, but often heroic struggles to live up to them. For progressives to recover faith in their country, they don’t need to avert their eyes from its dark side. But they likewise cannot turn away from America’s world-historically unique promise — and the immense amount of good which commitment to that promise has made possible, both here and all around the world.

To end their complicity in the spreading despair that is threatening the future of liberal democracy, progressives need to look inward and recommit to rekindling their own faith. Too many in their ranks have succumbed to despair themselves, alienated from the modern world and from their own country. There is only one way out: to choose to say yes, in spite of everything.

I think this question of faith is a key part of what you’re calling the permanent problem. To me the issue is that people have an intuition, often not consciously realized, that their life has no purpose. If you don’t have a reason to put up with this flawed world, regardless of how much it has improved materially, then why do it? Material comfort is a hygiene factor, not a substitute for purpose. We’ve moved up Maslow’s hierarchy to belonging, esteem, and self-actualization, and it’s a disaster. If there isn’t a reason to put up with the frustrations and disappointments of life, then why not line up behind a charismatic bully and burn it all down? At least that feels better than silently dissolving into nihilism. You are right that people need something like a religion, but our Freudian-tinged distrust of the subjective self, which is fair given the history of religious insanity in this world, prevents people from taking even a timid step toward an internal sense of meaning. As a committed Buddhist who sees life as a spiritual evolution occurring in a physical world explained by science, I don’t have this problem, my life is chock-full of meaning and purpose. I don’t have a disconnect between my education and spirituality. But, my subjective understanding of my life’s purpose would be considered delusional by many educated people. We have been taught that nothing true or meaningful can come from the deeper layers of the psyche, that it will never reconcile with our scientific understanding. This is the real disaster, because we will be unmoored until we overcome this bias.

beautiful work. nothing more to add.